The boy braked his bicycle on the bridge over the creek and stood straddling the frame. “What are you doing here?”

As I adjusted out of the mildly altered consciousness that comes from a long, peaceful run, I continued stretching my calf muscles, listening to the stream’s soft burbling, the autumn trees rustling, and studied my interrogator. He was about ten years old, with a stocky build, short hair and wire-rimmed glasses. His question wasn’t unfriendly—not as if he owned the park, but more of an inquiry into what other people came here for.

“I just ran four miles,” I said, “and now I’m stretching my legs.”

“Four miles?” His eyebrows shot up. “I can’t even run one.”

“It took me a while to build up to four. I didn’t run that far when I first started running.”

The boy asked what it felt like to run four miles and I said it was beautiful, being outdoors and quiet, moving through nature. It’s hard to describe the spirituality of running and I didn’t do a very good job of it. He said it must be a good workout. I agreed. He rode around a little while I finished stretching, and then pedaled beside me as I walked through the parking lot toward my neighborhood.

“What was it like the first time you ran?” he asked.

I told him a shortened version of the story that follows.

I’d been visiting the Apache reservation in Mescalero, New Mexico. A friend informed me that there would be a five-K and 10-K race the next morning, then looked me in the eyes and said “See you there.”

He and his girlfriend would be running, but I could tell he didn’t mean I would be there to cheer them on. He meant I would be running. I took the challenge and ran the five-K. At the time, I lived at sea level in the Tidewater region of Virginia, and Mescalero is 7,500 feet above that. Being an aerobics teacher, I was in good shape, but until that day I wasn’t a runner. I struggled uphill at that altitude, but the singer for the Navajo Nation Dancers kept cheering me on. His group had come for the powwow, and we had met briefly and chatted while waiting for the race to start. He couldn’t remember my name, only where I was from, so he shouted, “Go, Virginia! You can do it!”

I came in second for my age group, and I was hooked. Not on racing, but on the Apache concept of spiritual running. This race was not just any race, but a community event to promote health and traditional culture, timed to go with the four-day Dances of the Mountain Gods and the girls’ coming of age ceremony. My friend who convinced me to run had told me about spiritual running when we first met, and before the race started I got to know a number of other people who ran for cultural reasons. That was almost twenty years ago. and I never lost my love for running.

The boy in the park listened to the short version of this story attentively. We chatted a little longer. He concluded that he would still prefer bicycling and then pumped his way up the steep hill, wishing me a good day and saying, “See ya.”

There was a synchronicity to this encounter. Back in 1998, I made friends with the man who got me to run that first race by striking up a conversation with a stranger. I was stuck in an airport due to a delayed flight, and as I walked to pass the time, I noticed him sitting cross-legged on the floor rather than in a chair in one of the gate areas, and was intrigued by the writing on his T-shirt. It read: All Apache Nations Run Against Substance Abuse. I was doing research in graduate school about using traditional culture to combat modern health problems in Native communities. The idea of people running all the way from the various Apache nations, from Oklahoma and Arizona and New Mexico, to gather at one chosen reservation, was inspiring. We talked a while, and he invited me to visit Mescalero later that year and put me in touch with a medicine woman who could help with my research.

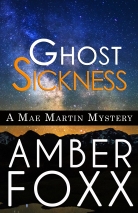

On subsequent trips, I ran the five-K several more times. At the time, I was thinking about writing an  academic paper, not fiction, but years later these races, the powwows, and the ceremonies inspired many of the scenes in Ghost Sickness. By the time I wrote the book, I had a lot of experiences to draw from.

academic paper, not fiction, but years later these races, the powwows, and the ceremonies inspired many of the scenes in Ghost Sickness. By the time I wrote the book, I had a lot of experiences to draw from.

My new young acquaintance’s friendly curiosity makes me think he has what it takes to be a writer. He has his own view—prefers biking to running—but he wanted to know what I thought and felt as a runner, and not because he planned to start running. He simply wanted to know. That’s a writers’ mind, or an actor’s or a psychologist’s. He asks: What’s it like to be someone who is not like me?